Spring 2007

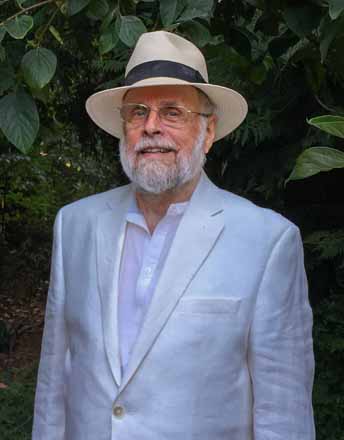

Instructor: Paul Brians

All of the study guides and other materials for this class are available in WebCT on the Web at https://webct.wsu.edu/ As soon as possible, you should go to this page and log in using your campus network ID and password and begin your work. Browse through the individual links to individual online readings, and other materials. Note that the dates for off-campus students sometimes differ slightly from on-campus students. The “Assignments” listed in WebCT are arranged to work with the off-campus students. On-campus students need to use the on-campus syllabus to determine when each assignment is due; you cannot rely on the each assignment matching a week of class. Be careful to read ahead in the syllabus so you see what assignments are coming up. Don’t wait until the night before class.

Please be aware that although WebCT is not open to the world at large, access is being provided to a few support personnel in the library and Student Computing Services. This warning is required by privacy regulations.

Note that if you work only from a printed-out version of this syllabus, you will lack many important hyperlinks. Always check the online syllabus when doing your assignments.

You will need to use a computer connected to the Web to read and print out these materials. You can use the various student labs on campus for short periods by paying an hourly fee, but you will be doing so much Web work in this class that it may be worth getting a semester pass. The cheapest access to a lab on campus is the 1-credit pass/fail course, English 300. If you have a wireless laptop, it can be used in several classroom buildings on campus to access the Web, including the library; but you will need to download the VPN software which will allow you to use the campus system.

Students are responsible for reading assignments and for preparing answers to the related on-line study questions before coming to class on the dates noted. Written assignments marked with an asterisk (*) are due on the date next to or above the asterisk. Besides the short papers noted here, you must also attend and report on a cultural event relating to the European 18th and 19th centuries. A list of acceptable events will be provided in class.

There will be many students taking this class remotely through the Distance Degree Program. On-campus and off-campus students will read and respond to each other’s work. On-campus students have work due twice a week. Because Pullman students do more assignments and take part in class discussion, less lengthy contributions for some assignments are required for them. Some of the off-campus assignments differ from the on-campus ones.

January

9: Introduction

Before class next time log into WebCT and write a brief description of yourself in the discussion titled “Introductions.” Videotape: The Art of the Western World, 5: Realms of Light—The Baroque [12395] (The Baroque: Bernini, Cortona, Caravaggio, Borromini, Fischer von Erlach,Velázquez, Vermeer, Rubens, Rembrandt, etc.). View tape in class, take notes, do assigned reading for the next class in WebCT before coming to class.

11: Read the “Course Introduction” Online.

Music: Pachelbel, Vivaldi, Handel. Take notes in class, do assigned writing in WebCT under Week 3: “Baroque Music.”

Read “The Enlightenment” and write at least 50 words about some aspect of the Enlightenment discussed there in the WebCT threaded discussion for this assignment in Week 1.

16: Do this assignment only after having read “The Enlightenment” and done the assigned online writing. Using the on-line Study Guide, then read Voltaire: Philosophical Dictionary: have the following articles read and notes taken about them to turn in at the beginning of class, at least 50 words covering more than one or two articles: Abbé, Ame, Amour-propre, Athée, athéisme, Beau, beauté, Bien (tout est, Bornes de l’esprit humaine, Catéchisme chinois, Certain, certitude, Chaîne des évenements, Credo). Before next time, do the assigned on-line writing for Voltaire Reading Assignment #1 in WebCT (in Week 2), and try to answer as many of the study questions in the Study Guide as you can as you go along.

18: Film: Knowledge or Certainty [1617] Before coming to class, read the online study guide; during the film, take notes; after class, do the assigned online writing in WebCT (in Week 2).

23: Music Lecture Videotape #2 [r472]: Bach. Do a second writing assignment in the threaded discussion called “Baroque Music_” in WebCT in Week 3, this time about the music by Bach you’ve heard.

25: Voltaire: Philosophical Dictionary: have the following articles read and notes taken about them to turn in at the beginning of class, at least 50 words: Éagalité, Enthousiasme, État, gouvernements, Fanatisime, Foi, Guerre, Liberté de pensée, Préjugés, Secte, Théiste, Tolérance, Tyrannie. Before next time, do the assigned on-line writing for Voltaire Assignment #2 in WebCT in Week 3, and try to answer as many of the study questions in the Study Guide as you can as you go along.

30: Library session, introduction to the research paper.

February

Sign up for library research topics. Be sure to attend. This is not a general library orientation, but a specialized presentation on sources you will need to use for doing this assignment. Look at “Suggested Research Topics for Humanities 303” online before coming to class and tentatively identify two or three topics you would like to work on. You may make up your own topic with my permission. See me first.

Although it is aimed primarily at off-campus students, you will also find much useful information in the Web page “Research Paper Assignment.”

First paper due, on Voltaire’s Philosophical Dictionary, 600 words. Be sure to read “Helpful Hints for Writing Papers” before beginning this assignment. Design your own topic or choose one of the following, using details from Voltaire which demonstrate your understand of his writings: freedom, free will and determinism, religion, tolerance, government, relativism. You may argue with him, but only if you present fully all relevant evidence on both sides. You must use material from two or more articles. If you have trouble choosing a topic or are uncertain whether your topic is acceptable, ask for help!

1: Read the introduction to Romanticism and do the assigned writing in WebCT in Week 4.

Using the Faust Study Guide, read Job: Chapters 1 & 2; Goethe: Faust: Introduction, Prologue in Heaven. Write notes to turn in, do online writing for Goethe Assignment #1 in WebCT in Week 4.

6: Videotape: The Art of the Western World, 6: An Age of Reason, An Age of Passion [12396] (Antoine Watteau: Departure from Cythera,Robert Adams, François Boucher, Jean-Baptiste Greuze, Jean-Baptiste Chardin, Nicolas Poussin, Jacques Lemercier: Palais-Royal, Charles Perrault: Colonnade of the Louvre, Germain Soufflot: Panthéon, Giambattista Piranesi: drawings of Paestum, Jacques-Louis David: Death of Marat & The Sabine Women, Vignon: La Madeleine, Dominique Ingres: Odalisque, Jean-Antoine Gros, Francisco de Goya: The Horrors of War, Géricault, Eugène Delacroix: Liberty Leading the People, Théodore Géricault: The Raft of the Medusa) Take notes during videotape, do online writing in In WebCT in Week 5.

8: Goethe: Faust: Night, Before the City Gate, both scenes titled “Study.” Write notes to turn in, do online writing for Goethe Assignment #2 in WebCT in Week 5.

13: Music Lecture Videotape #3 [r485]: Mozart, Beethoven. Take notes during presentation, do online writing before next class in In WebCT in Week 5.

Research paper proposal and annotated bibliography due: a paragraph outlining the topic and a list of sources to be used, with comments for each explaining why the sources will be useful to you. Be sure to include all three elements: the proposal itself, the list of sources, and the comments. If you have not already done so, read “The Research Paper.”

15: Goethe: Faust: Witch’s Kitchen, Street, Evening, Promenade, The Neighbor’s House, Street, Garden, A Garden Bower, Wood and Cave, Gretchen’s Room, Martha’s Garden. Write notes to turn in, do online writing for Goethe Assignment #3 in In WebCT in Week 6.

20: Videotape: “The Artist Was a Woman” [VHS 18321]. Take notes during class, do online writing in the “Women Artists__” threaded discussion in In WebCT in Week 6.

22: Goethe: Faust: At the Well, City Wall, Night: Street in Front of Gretchen’s Door, Cathedral, Walpurgis Night, Dismal Day, Night, Open Field. Write notes to turn in, do online writing for Goethe Assignment #4 in WebCT in Week 7.

27: Note: during the next week and a half, you have little homework other than to write your paper on Faust. This is the time that you are expected to use to also read Zola’s Germinal. Because it is a long book, you may want to start reading ahead now and not put it off until the week when it is due.

Goethe: Faust: Dungeon, Charming Landscape, Open Country, Palace, Deep Night, Midnight, Large Outer Court of the Palace, Entombment, Mountain Gorges: Forest, Rock and Desert. Write notes to turn in, do online writing for Goethe Assignment #5 in WebCT in Week 8.

Music Presentation Online on Women Composers. Listen to the music and read the notes on Women Composers on reserve in Griffin for Hum 303 using RealAudio, take notes, and do the assigned online writing in WebCT in Week 10. Have this assignment completed by next time (Oct. 16).

March

1: Before class, read the Study Guide for La Traviata.

Music Lecture Videotape #5 [r521]: Romanticism: Berlioz, DVD: Verdi: La Traviata (beginning). Take notes during presentation, do online writing before next class in WebCT in Weeks 7 & 8.

6: Verdi: La Traviata (conclusion) [11765], beginning.

Women composers presentation. Take notes during presentation, do online writing before next class in WebCT in Week 8.

Second paper due, on Goethe’s Faust, 1200 words. Counts 20 points. Design your own topic or choose one of the following:, remembering that you will be expected to define your topic further, since most of these are very broad: Faust and Mephistopheles , Faust and Gretchen, Thought vs. Action, Religion, Humor, Music, Magic, Classical Mythology. Again, if you have trouble choosing or defing a topic, ask for help.

8: Read “Realism and Naturalism” and do online writing in WebCT in Week 7. Zola: Germinal: Parts 1-3. Use Study Guide and take notes to turn in, do online writing for Zola Assignment #1 in WebCT in Week 8.

20: Zola: Germinal: Parts 4-5. Use Study Guide and take notes to turn in, do online writing for Zola Assignment #2 in WebCT in Week 10.

22: Zola: Germinal: Part 6-7. Use Study Guide and take notes to turn in, do online writing for Zola Assignment #3 in WebCT in Week 11.

27: Read “19th Century Russian Literature” and do online writing in WebCT in Week 12. Dostoyevsky: Notes from Underground: Afterword, pp. 90-123. Take notes using Study Guide, do online writing in the Dostoyevsky threaded discussion in In WebCT in Week 12.

29: Dostoyevsky: Notes from Underground: pp. 123-203. Take notes using Study Guide, do online writing, do a second online in the Dostoyevsky threaded discussion n WebCT in Week 12.

April

3: Videotape: The Art of the Western World, 7: A Fresh View: Impressionism and Post-Impressionism [12397] (Courbet, Degas, Manet, Monet, Renoir, Whistler, Pissarro, Sargent, Cassatt, Gauguin, Seurat, Van Gogh, Signac, Bernard, Toulouse-Lautrec, Valadon, Cézanne), Impressionist art slides. Do the assigned writing in In WebCT in Week 13. Research paper due; 1200 words minimum. Re-read “The Research Paper” online and “Helpful HInts for Writing Class Papers,” particularly checking to make sure you are following proper procedures for citing sources and quoting. Remember, you must cite sources for all facts and ideas, not just words quoted. 20 points; required revised version due May 4.

5 Read “The Influence of Nietzsche,” taking notes, do online writing in In WebCT in Week 13. Nietzsche: Thus Spoke Zarathustra: Translator’s Preface, pp. 9- 28. Take notes using Study Guide, do online writing for Nietzsche Assignment #1 in In WebCT in week 13.

10: Nietzsche: Thus Spoke Zarathustra: pp. 28-54. Take notes using Study Guide, do second online writing for Nietzsche Assignment #1 in In WebCT in Week 13.

12: Nietzsche: Thus Spoke Zarathustra: pp. 54-79. Take notes using Study Guide, do online writing for Nietzsche Assignment #2 in In WebCT, Week

- Music Videotape Lecture 6 [r559]: Impressionist Music: Debussy & Ravel. Take notes during presentation, do online writing in In WebCT in Week 13.

19: Read Misconceptions, Confusions, and Conflicts Concerning Socialism, Communism, and Capitalism. Take notes, do online writing in In WebCT in Week 15. Read Introduction to 19th-Century Socialism. Take notes, do online writing in In WebCT in Week 15. Karl Marx & Friedrich Engels: The Communist Manifesto: Prologue, Section 1 . Using Study Guide, take notes, do online writing in In WebCT in Week 15.

24: Karl Marx & Friedrich Engels: The Communist Manifesto: Sections 2 & 4. Karl Marx & Friedrich Engels: The Communist Manifesto: Section 2. Using Study Guide, take notes, do a second online writing in In WebCT in Week 15.

26: Music Lecture 7 [r569]: Early 20th Century music, Course evaluation. Write about music in In WebCT in Week 14.

May

2 Third paper due, on Zola, Dostoyevsky, Nietzsche, or Marx, 600 words minimum. Counts 10 points. If you wrote on one of these authors for your research paper, choose a different one to write on for this assignment. Sample topics on Germinal: Women, Changes in the Miners, Sexuality and Nature, The Mine as Monster. Sample topics on Dostoyevsky: The UM’s Assault on the Enlightenment, The Concept of Freedom, Self-Hatred, Fear of Love. Sample topics on Nietzsche (be sure to use more than one passage from the book): Relativism, Freedom, Principal Characteristics of the Overman, Nietzsche and Christianity, Romantic and Enlightenment Aspects. Sample topics on Marx: The Nature of Class Struggle, The Role of the Bourgeoisie in Transforming History, Marx’s Answers to his Critics, Advantages and Disadvantages of Communism as Described in the Manifesto.

Final date for cultural event.

All revised papers due, including revised research paper. You must attach the graded first draft to your research paper when you turn it in.

Textbooks for this course (please do not substitute other editions or translations):

If your financial aid is delayed, borrow money if you must to buy the textbooks. You cannot begin the course without the Voltaire in hand; and other books will be unavailable late in the semester. Buy them all as early as possible. If the Bookie is out, try Crimson and Gray on Bishop Boulevard. Do not substitute other translations for these.

Voltaire: Philosophical Dictionary, translated by Theodore Besterman

Goethe’s Faust, translated by Walter Kaufmann

Zola, Germinal, trans. Pearson. Penguin.

Dostoyevsky: Notes from Underground, translated by Andrew R. MacAndrew

Nietzsche: Thus Spoke Zarathustra, translated by Walter Kaufmann. (Note Penguin also publishes other translations that are not as good_ be sure to get the Kaufmann. DO NOT USE the 1892 public-domain translation by Thomas Common.)

Marx & Engels: The Communist Manifesto (International Publishers)

Paul Brians’ Policies Spring 2007

Please read this material carefully and save it.

Office: 202H Avery Hall

Direct phone: 509 335-5689, English Dept. phone: 509 335-2581, FAX: 509 335-2582, email: paulbrians@gmail.com

Home Page: https://brians.wsu.edu/

Common Errors in English: https://brians.wsu.edu/common-errors-in-english-usage/

If I am not in, the phone may be answered by the automated voice mailbox service. Please leave a message including your name and phone number (speaking s-l-o-w-l-y, please).

Study questions:

For each of the reading assignments, the study guide in WebCT contains a series of study questions which I want you to think about. It is your assignment to answer as many of these questions as you can while you read, and to write the assigned amount on each week’s reading in WebCT Cover more than a couple of questions, and make sure you can discuss all parts of that week’s assignment—not just the beginning. Show that you are thinking seriously about these questions. Typically you are asked to write something of your own, then respond to at least one other person. These WebCT assignments are graded pass/fail (I will let you know quickly if you have done an inadequate one). The idea is to promote class discussion online. This is where you will be interacting with off-campus distance-learning students as well. When other members of the class ask questions, try to reply to them. You are welcome to keep up the discussions we start here as long as you want, but please remember to be polite. Not everyone has the same views and assumptions. You must miss or fail no more than five of these Speakeasy discussion assignments to pass the course.

Papers:

For this course you will be required to write a series of brief papers. Note the length specified by your course syllabus, which does not include notes or list of sources. Minimum paper lengths are so extremely short in this class that anyone desiring a high grade would be advised to write a somewhat longer one. Any paper shorter than the minimum assigned will receive a 0 for an incomplete assignment. Except for meeting the very low minimum number of words, don’t concentrate on length, but try to make your papers as detailed, well-organized, and interesting as possible. All papers must be typed on a computer and printed out. If you have trouble with your printer, you may bring in the paper on a disk or send it to me by e-mail attachment. Printer problems are never an excuse for not getting a paper in on time. If you use a typing service, please proofread its work carefully; you are responsible for all errors. The regular papers are not necessarily research papers, and it is possible to receive maximum points on a paper without doing research for it, although papers incorporating good library work will normally receive higher grades. Suggested topics are listed on your syllabus. You should choose a topic you are particularly interested in, not try to guess what I want you to write. When I can learn something new from a paper, I am pleased. If you have trouble thinking of a topic, ask me for help. I am also happy to look over rough drafts and answer questions about proposed topics. In addition, one paper per semester will be a required library research paper incorporating information gathered from scholarly books and articles (not just Web pages and reference books like dictionaries and encyclopedias). For more details on how to write papers for this class, see “Helpful Hints for Writing Class Papers.” For details on how to write the research paper for this class, see the page entitled “Research Paper Assignment. Papers are due at the beginning of class on the day specified in the syllabus. Do not cut class to finish a paper. Papers may always be submitted before the due date if you wish. There is no midterm or final examination in this class.

The following elements are taken into consideration when I grade your papers: 1) You must convince me that you have read and understood the book or story. 2) You must have something interesting to say about it. 3) Originality counts—easy, common topics tend to earn lower grades than difficult ones done well. 4) Significant writing (spelling, punctuation, usage) errors will be marked on each paper before it is returned to you. If there are more than a few you must identify the errors and correct them (by hand, on the same paper, without retyping it) and hand the paper back in before a grade will be recorded for you. 5) I look for unified essays on a well-defined topic with a clear title and coherent structure. 6) I expect you to support your arguments with references to the text, often including quotations appropriately introduced and analyzed (but quote only to make points about the material quoted, not simply for its own sake). 7) You must do more than merely summarize the plot of the works you have read. See my “Helpful Hints” online for more information.

Research papers are especially graded on proper use of sources and coherence. Research papers when first handed in must be the complete product: minimum length, notes, bibliography, etc. If you want to have me look at an incomplete rough draft before the due date, I will be happy to do so. Your research should be complete before the due date for the first draft.

Late Papers:

If you think you have a valid excuse (medical, etc.) for not getting a paper in on time, let me know in advance (phone) if you can. Choosing to work on other classes rather than this one is never an acceptable excuse for handing in a paper late. Because of my make-up policy (see below), it almost always makes more sense to send in even a poorly-done, rushed paper than none at all. Papers sent in late with no excuse will not receive a passing grade. To pass the course you must hand in all assigned papers. Do not assume you will be allowed to hand in work late. Pay careful attention to due dates on the syllabus.

Revised papers:

You may not make up a paper which you have failed to hand in. However, if you do hand in a paper and are dissatisfied with your grade, after consulting with me, you may revise your paper and have your grade raised if it is significantly improved. You are required to revise the research paper at least once. Other revisions will be handled on an individual basis, and limits will be set as to the number of revisions allowed and the time allowed to hand them in. Simply substituting phrases that I have suggested to improve your writing does not result in an improved grade. You have to make the sort of substantial changes I suggest in the note I make on your paper.

Grading Policy:

Again, to pass the course you must complete all papers. The research paper and its revision especially are not optional. Note that you will not receive a letter grade on your research paper until after it has been revised in response to my initial comments on it, especially the final comments written at the bottom of your paper.

Grading of WebCT participation.

Attendance and participation in the course are measured by the contributions you make to in WebCT plus the notes you turn in at the beginning of class. Together the written contributions count as 20% of your grade. Contributions are graded on a pass-fail basis. Assume they have been counted unless I make a response to what you have written saying it is inadequate.

The number of points for each paper is indicated on the syllabus with the paper assignment. For a 10-point paper, 9.5 or above=A, 9.0-9.4=A, 8.8-8.9=B+, 8.3-8.7=B, 8.0-8.2=B-, 7.8-7.9=C+, 7.3-7.7=C, 7.0-7.2=C, 6.5-6.9=D, anything below 6.5=F. Double these numbers to get the appropriate scale for a 20-point assignment.

Voltaire paper: 10 points

Faust paper: 20 points

Third paper: 20 points

Research paper: 20 points

Cultural event report: 10 points

Speakeasy contributions: 20 points

Total: 100 points.

Standards for grading papers:

All assigned papers must be turned in to pass the course.

A Topics are challenging, often original; papers are well organized, filled with detail, and demonstrate a thorough knowledge of the topic. Examples are chosen from several portions of the work. Opinion papers are carefully argued, with detailed attention being paid to opposing arguments and evidence. Papers receiving an “A” are usually somewhat longer than the minimum assigned, typically a page or so longer, though this all depends on the compactness of your writing style—a paper which is long and diffuse does not result in a higher grade and a very compact, exceptionally well-written paper will occasionally receive an “A.” The writing should be exceptionally clear and generally free of mechanical errors. An “A” is given for exceptional, outstanding work.

B Topics are acceptable, papers well organized, containg some supporting detail, and demonstrate an above-average knowledge of the topic. Examples are chosen from several portions of the work. Papers are at least the minimum length assigned. Opinion papers are carefully argued, with some attention being paid to opposing argument and evidence. Writing is above average, containg only occasional mechanical errors. A “B” is given for above-average work.

C Topics are acceptable, but simple. Paper are poorly organized, containg inadequate detail, demonstrating only partial knowledge of the topic (focusing only on one short passage from a work or some minor aspect of it). Papers are at least the minimum length assigned. Opinion papers contain unsupported assertions and ignore opposing arguments and evidence. Writing is average or below, and mechanical errors are numerous. Paper does not appear to have been proofread carefully. A “C” is given for average work.

D Inappropriately chosen topic does not demonstrate more than a minimal comprehension of the topic. Papers are at least the minimum length assigned. Opinion papers contain unsupported assertions and ignore opposing arguments and evidence. Writing is poor, filled with mechanical errors. Paper does not appear to have been proofread. A “D” is given for barely acceptable work.

F Paper is shorter than the minimum length required. Topic is unacceptable because it does not cover more than an incidental (or unassigned) portion of the work or does not reveal a satisfactory level of knowledge . Generalizations are unsupported with evidence and opinion papers contain unsupported assertions and ignore opposing arguments and evidence. Writing is not of acceptable college-level quality. Paper does not appear to have been proofread. An “F” is given for unsatisfactory work.

Plagiarism:

Plagiarism is: 1) submitting someone else’s work as your own, 2) copying something from another source without putting it in quotation marks or citing a source (note: you must do both), 3) using an idea from a source without citing the source, even when you do not use the exact words of the source. Any time you use a book, article, or reference tool to get information or ideas which you use in a paper, you must cite it by providing a note stating where you got the information or idea, using MLA parenthetical annotation. No footnotes are used in papers for this class. You do not need to cite material from classroom lectures or discussions. If you are not certain whether you need to cite a source, check with me in advance. See “Helpful Hints” and Barnet (pp. 73-86) for details on how to cite sources. Anyone caught plagiarizing will receive an “F” for the entire course (not just the paper concerned) and be reported to Student Affairs. If you feel you have been unjustly accused of plagiarism, you may appeal to me; and if dissatisfied, to the departmental chair.

Cultural Event Assignment:

Humanities 303 students will attend a cultural event relating to the 18th or 19th centuries and report on it in a 600-word paper which will be graded like the other papers in the course (worth 10 points). Announcements of qualifying events will be posted in The Birdge. Substitutions may be arranged for students not living near a site where qualifying cultural events are taking place. Let me know as soon as possible what you have decided to do for your cultural event.

Disability Statement

Reasonable accommodations are available for students who have a documented disability. Please notify the instructor during the first week of class of any accommodations needed for the course. Late notification may cause the requested accommodations to be unavailable. All accommodations must be approved through the Disability Resource Center (DRC) in Administration Annex 206, 335-3417.

E-mail

I will be sending out occasional class announcements via e-mail using the WSU system. However, this means that you must have a valid e-mail address that you actually use in the WSU directory, though much important official mail, like library fine notices, is sent out using this system. To make sure you are listed in the directory go to http://www.wsu.edu/ and click “Find People,” and search for your name (last name first, no comma).

Then click on “ADDRESS & E-MAIL_” on the left-hand side of the page and click on either “Change your email destination address.” If you want a free WSU e-mail account, create an address in myWSU.

Version of January 2, 2007

All assigned papers (including the research paper—both first and revised drafts) must be completed to pass the course.