Terminator vs. Terminator

elizabeth.wassonNuclear Holocaust as a Video Game

Paul Brians

Professor of English

Washington State University

Pullman, WA 99164-5020

The following piece was written in 1991 for a proposed special issue of a journal which abandoned the idea so many months later that the article had lost its immediacy. I didn’t feel like revising it according to their suggestions for publication as an independent piece because their consultants’ views of the Terminator films differed drastically from mine. I am no longer doing research in this area, but I think the article may still be of interest to some readers, so am posting it here.

This article has been translated into German: Terminator vs. Terminator: Nuklearer Holocaust als Videospiel.

Translations of this article also available in Czech and Dutch.

Copyright Paul Brians 1995

You can write me at: paulbrians@gmail.com.

Home Page

Back in 1984 I participated in a conference on war in fiction at the Monterey Institute of International Studies. Part of the program was a screening of Philippe de Broca’s 1967 antiwar classic King of Hearts . It struck me as sadly irrelevant to the mood of young people in the eighties, so I skipped the session to take in the latest hot flick in a downtown theater: The Terminator, starring Arnold Schwarzenegger. Though I am not a fan of “action” movies, I hoped to learn something about what was exciting contemporary audiences.

What I experienced surprised and angered me. It was not the relentless, brutal violence and manipulative terror—these I expected. But I was taken aback by the way in which the predominantly youthful audience gleefully rooted for the Terminator, whose purpose was after all the total extermination of the human race through the murder of the destined mother of its future savior, John Conner. I don’t think my experience was unique. David Edelstein, reviewing the film for the Village Voice, noted that when the Terminator appeared “the audience whoops and applauds.”1 I shouldn’t have been surprised. The Terminator had villain written all over him in bold block letters; but audiences who gleefully cheer the monstrous slasher Freddie in the Nightmare on Elm Street films cannot be expected to shift emotional gears just because the target is enlarged to embrace the entire human community.2

The popularity of the Terminator concept is also evidenced by the popularity of several series of comic book adaptations featuring plenty of graphic violence.3 Schwarzenegger’s signature line “I’ll be back!” became a catch phrase widely and humorously quoted, but more as a promise than a threat: there is more exciting action to come.

My second reaction was to a disturbing subtext I perceived in the film itself. It struck me immediately as a survivalist fantasy arguing that nuclear war is inevitable and that our only hope lies in gathering skill in using personal violence to fight the wars which lie beyond Armageddon. Those crazies who busily stockpile food and ammo, expecting to fight indifferently the Russkies, their neighbors, or the U. S. Army had seen their vision endorsed by Hollywood.

Wrestling with my emotional revulsion against this message and the audience’s reaction, I was inevitably struck by a seeming contradiction. If the film was preaching survivalism, why was the audience cheering for its own annihilation?

Critics are routinely contemptuous of films such as this (Mad Max: Beyond Thunderdome is another good example) because they simultaneously seem to reject violence (the war which threatens human sur vival) and glorify it (the battles after the war).4 But on the simplest level this is not necessarily a fatal contradiction. A gory tale like The Iliad or The Song of Roland can both revel in and deplore war without raising such cavils; and only pacifists are prone to equate personal violence with worldwide warfare. Not that The Terminator is likely to join anybody’ s canon of masterpieces, but the common wisdom is that if a good deal of killing is morally acceptable to prevent even greater amounts of killing.

No, the contradictions embedded in The Terminator are more complex, and much more threatening. Most of humanity is about to die, and there is nothing whatever we can do about it. Why is this an acceptable subtext for an escapist entertainment?

There are several possibilities. Spectacular screen violence is so appealing to adolescent audiences (especially but not exclusively males) that they may not even notice the context in which that violence is embedded. Certainly most viewers of Mad Max: Beyond Thunderdome seemed to miss entirely its anti-nuclear war message, although it was much more prominent than the same message in The Terminator. But it may also be the case that the audience did absorb on some level the prophecy of doom delivered by the film but found it attractive and exciting out of the sort of adolescent nihilism that fuels the immense popularity of heavy metal bands and super-violent comic books. Today’s rebels without a cause are mostly comfortably well-off youth whose restlessness scorns idealism or radicalism and glories in images of destruction for its own sake. Kids often amuse themselves with violence these days, though their rebellion is actually quite trivial and easily domesticated and marketed, of course. Another possibility is that such films are just another vehicle for adolescent bravado: viewing the fall of civilization is the cinematic equivalent of an exceptionally terrifying roller coaster ride: the only relevant question is can you take it?

I suspect that each of these explanations has some truth in it; but I am convinced that there is another dynamic at work here which has deep connections with the way Americans have mythologized nuclear war. When they have not simply repressed the threat from consciousness as they usually have the next most popular attitude has always been fatalism. From the early days after Hiroshima and Nagasaki onward, it was commonly accepted that atomic bombs could, and one day might, “destroy the world.” By far the most commonly expressed sentiment about nuclear war is “If the bomb goes off, I hope I’m at ground zero.”

Given the relatively trivial numbers of these weapons in existence during the early years of the cold war, the power of this mythology is impressive. Of course governments encouraged such attitudes by assuring their citizens that nuclear weapons are so apocalyptic as to make the most insane enemy blanch at the thought of attacking another nuclear power. But such reassurance entails its own subversion. Clearly in the atomic age it makes no sense to feel safe because our enemies are terrorized. The Cold War was not called a “balance of terror” for nothing. Forced to think about the prospect of annihilation, people resorted to a standard psychological mechanism familiar in connection with thinking about death: accepting it as inevitable and putting it out of mind as much as is possible.

The popularity of Dr. Strangelove is probably to be attributed at least in part, paradoxically, to its comfortingly nihilistic message: our leaders are insane, there are no effective controls, we’re all doomed, so we might as well have a good laugh before we go. Although it is a fine film in many ways, Dr. Strangelove is one of the most profoundly disempowering tales ever spun about nuclear doom. Similarly, much of the appeal of On the Beach resides in the relentless way in which death marches across the globe, sparing no one. Depicting nuclear war as universal extinction is the next best thing to not thinking about it at all. We manage to live with the prospect of our personal deaths because we know death is universal and inevitable. Applying the same mechanism to reacting to the arms race, we manage to muddle on, released from responsibility. Nuclear war as a problem has been defined out of existence. It has become instead a fact of life.

The problem is, of course, that nuclear war is not the same thing as death; and while young people in the eighties were flirting with apocalyptic imagery, an accelerated arms race was making a real apocalypse ever more likely.5

Another striking political message of The Terminator is an apparent endorsement of the National Rifle Association’s position on gun control. When a gun dealer explains the required waiting period for certain weapons, the Terminator short-circuits the process by shooting him dead on the spot. Obviously when guns are outlawed, only outlaws will have guns.

Several critics have commented on the anti-machine message delivered by the film. Karen B. Mann lists the the malevolent technology which dominates the world of the film and embodies the reality of the threat symbolized by the Terminator: ” hair dryers, electric curlers, Walkmans, TVs, radios . . . the essential telephone answering machines, technology dominates meaning relationships and transactions in the film.”6 America’s love/hate relationship with technology is broadly satirized throughout the film, and cleverly alluded to in the name of the dance club where Sarah takes refuge from Reese: Tech Noir. On one level The Terminator is a descendant of such anti-technological satires as Chaplin’s Modern Times or Jacques Tati’s Mon Oncle. The politics of this sort of satire are Luddite rather than Marxist. The shallowness of The Terminator’s satire is revealed by the fact that the machine is ultimately defeated by other machines (a point even more clearly made in Terminator 2).

But The Terminator is more specifically about nuclear technology. Its basic premise that the defence network Skynet has launched a nuclear war in an effort to annihilate humanity seems borrowed from The Forbin Project .7 Both films mythologize nuclear weaponry as a modern-day Frankenstein’s monster: a misbegotten creation which turns on its creator. Their ancestry includes countless tales in which scientists have “gone beyond the limits of what man was meant to know” and which in the post-Hiroshima era have almost always been parables of atomic-age anxiety. But The Terminator is ultimately not truly an anti-nuclear war film precisely because it accepts the inevitability of such war, never suggesting that it might be in any way preventable. The arms race and the holocaust in which it logically culminates are givens, and mighty convenient givens for generating an exciting sense of impending doom and destruction.

Lillian Necakov, looking for progressive elements in the film, perceives Sarah Conner as an unconventionally assertive and powerful woman.8 Other feminist critics object. Margaret Goscilo asserts that Sarah “is a mere conduit of male power and supremacy between her son and her lover.”9 And Vivian Sobchack argues that the film justifies men’s refusal to take responsibility for child-rearing.10 According to Sobchak, Sarah is a strong, self-sufficient single mother who has not been truly abandoned because the dead father of her child still exists in a future and is forever returning to impregnate her in the past. Sarah’s strength exists only to absolve men of their responsibility to women and children.

In The Terminator, Sarah certainly doesn’t strike me as a pillar of strength; but Necakov was probably on to something; the next two thrillers made by James Cameron and his wife Gale Anne Hurd feature unmistakably powerful heroines. The heroine of Aliens is a courageous, skilled, and intelligent woman who destroys vicious monsters from space when the male soldiers have been wiped out because their macho attitudes got in the way of effective combat; and The Abyss features a brilliant, tough, and domineering female scientist.

Not that these characters are models of feminist correctness. They are also both physically attractive, and the latter might almost have been designed by a male masochist fantasizing the ideal dominatrix. Tough women are very hot stuff currently in a variety of popular media ranging from female body-builder competitions to comic books featuring leather-clad female assassins. It’s clear that contemporary male taste in erotic fantasy embraces models radically different from the traditional passive, submissive one.

Even so, Lindsey Brigman, the ruthless woman scientist in The Abyss, has to learn humility and tenderness from her sensitive, less assertive husband. Yet she does not surrender her competence or courage. It is notable that in this film husband and wife take turns risking their lives to save each other. The Abyss is an equal-opportunity, interracial, anti-military, pro-working class thriller. While certainly not a progressivist tract, The Abyss marks a large step in the continuing shift of Cameron’s films from the reactionary politics of The Terminator.

Thus I looked forward with great interest to the sequel, Terminator 2: Judgment Day. How could Cameron’s new politics be reconciled with his old themes? Would the subject of nuclear war be more prominent in the sequel? I was pleasantly surprised by the answers to both these questions.

I am not going to pretend that my generally positive reaction to the film is shared by everyone. Stanley Kauffmann, writing in The New Republic states that “The surprise is that a picture made to be exciting for 136 minutes is so unexciting most of the time.”11 Ralph Novak in People magazine found it “shamefully sadistic, achingly dull and totally predictable,” claiming that ” it rehashes the far superior 1984 original.”12

In contrast, Janet Maslin wrote in the New York Times, “Mr. Cameron has made a swift, exciting special-effects epic that thoroughly justifies its vast expense and greatly improves upon the first film’s potent but rudimentary visual style.”13 Reviewers for the LA Times and San Francisco Chronicle agreed.14

Clearly there is no point in insisting that a film that bores some viewers is in fact engrossing. Some viewers prefer the first film simply because they like the meaner, tougher Schwarzenegger in an unambiguously violent setting. I suspect that certain critics who prefer the first film are drawn to it by its anti-technological bias and repelled by the high-tech gloss of the computer-created special effects of the second one. It isn’t considered sophisticated to enjoy expensive dazzle and flash, and the first film is redeemed in their eyes by its low-budget grunginess.

But Cameron always wanted to make The Terminator a special effects film; he was prevented from doing so by a modest $6.5 million dollar budget.15 The success of the first film enabled him to make the sequel into the film that he had wanted to make all along, reportedly the most expensive ever made.16

Terminator 2 reworks a number of elements from the first film. Both open in a scene of future combat. A pair of time travellers—an assassin and his adversary—arrive naked amidst powerful electrical disturbances (which in Terminator 2 are even more strongly reminiscent of the scene of the creation of Dr. Frankenstein’s monster). The toughs Schwarzenegger confronts at the beginning of each film—punks in the first, bikers in the second—are the sort of convenient, disposable scum that serves as cannon fodder in all sorts of cheap men’s fiction. In both films, it is not revealed until well into the plot that the character which seems to be trying to kill Sarah is actually trying to protect her, though the extreme efforts at building suspense on this point in the second film were utterly vitiated by the massive publicity touting Schwarzenegger as the good guy in Terminator 2. The assassin in both films is shot for the first time just as he’s about to kill his victim. Even trivial details are repeated. Schwarzenegger drives a cop car in both. He slices open his arm in both. In The Terminator a truck driver is forced from his truck; in Terminator 2 a helicopter pilot is similarly forced from his vehicle. The little girl playing at shooting in the dismal future of The Terminator is echoed in Terminator 2 by the scene at a gas station in which a boy and girl pretend to shoot at each other, shouting, “You’re dead!”

But if in some ways Terminator 2 is more a remake than a sequel, in other ways it is a reply to the first film. Almost as if Cameron had been reading his feminist critics, the new Sarah Conner has lost every ounce of her early cute freshness and become a wiry bundle of nerves, bones and muscles. We first see her as she does chin-ups in her cell, looking nothing like the Lisa Lyons model of female body-building. She rages, claws and smashes through obstacles with a fearsome energy that is completely determined by her nightmare visions of the nuclear war to come. Unlike Ripley in Aliens, Sarah displays no motherly affection for the child she is so frantically trying to protect. She wants to save him because she has nightmares about the death of other children. When we are once tricked into thinking that she will at last hug him, she actually gives him a quick check for bullet holes and bawls him out for risking his life to rescue her. As an object of the male gaze, Sarah is a pretty startling sight.

Of course one could make out a case that, as is the case with other Cameron females, this is gender-bending to excuse male violence and insensitivity, telling men, “See, some women are like that too.” But Cameron seems to anticipate this objection by giving Sarah the widely-quoted speech in which she hails the CSM-101 as a better man than any of her other male partners. She may be less nurturing toward her son than the cyborg, but she appreciates his nurturance and loyalty. The fact is that Sarah is as sympathetic as she is disturbing because hers is the moral vision that informs the film, and that vision consists of a determination to prevent the nuclear holocaust which seemed so inevitable in The Terminator. Lindsey’s ruthlessness in The Abyss was “bitchy.” Sarah’s is heroic.

Terminator 2 constantly argues with criticisms of The Terminator. You didn’t like all that killing in the name of saving lives in The Terminator? Okay, we minimize the killing. You object that assassination is a lousy way to improve the world? This time around John gets to make just that point to his mother when she finds that she can’t cold-bloodedly shoot the scientist destined to create the robots who are destined to destroy humanity.

Most importantly, from my point of view, Terminator 2 rejects the nuclear fatalism of The Terminator. The point of this film is to prevent the nuclear war looming in the near future. Cameron explains his intentions an interview contained in Don Shay and Jody Duncan’s book on the making of the film:

I’ve tried to make people think about the unthinkable nuclear war. We have to if we don’t, we’re screwed. I believe that. So if I can sugar-coat it with a big epic action thriller and get people into the theaters and get them thinking about something that they wouldn’t otherwise, then maybe that does some good other than just making all of us a lot more money.17

As Oliver Morton notes, “Terminator 2 ‘s structure is an explicit denial of The Terminator’ s. Whereas the point of The Terminator is to reach that final scene and make the preceding film a necessary consequence of its ending, the point of Terminator 2 is to reach an ending in which neither that film, nor its predecessor, were necessary in the first place.”18

Of course this is contradictory, but contradictions are inevitable in any time-travel story that does not follow (like Woody Allen’s Sleeper ) the inexorably forward-pointing arrow of time. They succeed only by ignoring their own illogic, or like Terminator pointing it out only to dismiss it. Excessive literalism is fatal. After leaving the theater we may realize, for instance, that if the nuclear war has really been averted, John should not exist, since he is a product of that war. Sarah’s efforts to save his life could be seen as threatening his very existence. But both films discourage such speculation by keeping the diverting action going and letting the characters express their own bewilderment at the contradictions built into their story.

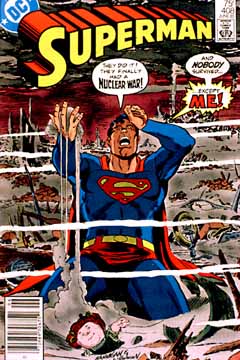

It’s no use carping as many critics have about Terminator 2′s logic. What is of some use is noticing the limitations of its attitudes toward nuclear war. For all its virtues, this film has some amazingly stupid things to say on the subject. The problem is not, as some have argued, that its vision of such a war is understated; it contains the most carefully researched, accurately depicted portrayal of a nuclear explosion in any film yet made.19 Its scenes of carnage put The Day After to shame. The only film to focus more closely on the effects of nuclear weapons in a graphic way is Shohei Imamura’s story of the Hiroshima bombing, Black Rain.

But its conscientiousness does not make Terminator 2 a smart film about nuclear war. The first obvious problem is that it uses that hoariest of bad science fiction film clichés: the crucial scientist whose elimination can save the world. The fact that the scientist is a brilliant, sympathetic black man may prevent us from noticing the cliché for a while, but it’s there. It’s true that the storyline does not really require his death–only the destruction of the microchips he’s been studying; but the point made by this variation on the myth is the same: science is the product of irreplaceable individuals, so one can uninvent a device by killing its inventor. As applied to the atomic bomb, this was early on proven a fallacy when the Soviet Union developed its own bomb (though Americans long clung to the myth that it couldn’t have done so without stealing our secret formulas). As the anti-nuclear-disarmament crowd never tires of repeating, you can’t uninvent the bomb. Terminators may be prevented: they don’t exist yet. Bombs do.

I stated earlier that the apparent contradiction that violence is used to prevent violence is not necessarily fatal. However, the problem with the tension between these two kinds of violence in Terminator 2 is that they do not seem to inhabit the same stylistic universe. Sarah’s visions of Judgment Day are overpoweringly horrific, her reactions to them intense and moving. The violence perpetrated by the two Terminators is cartoonish, often comic. The antics of the liquid-metal T-1000 strongly resemble those of the old comic book character Plastic Man (though today’s kids might think of him as an unusually supple Transformer). The Terminator was a pure escape film because the future nuclear war was barely sketched in, obviously only an excuse for the depiction of exciting action. In structure it was little more than a car chase film combined with the excitement of a shooting gallery where the targets keep bobbing back up after being hit.20

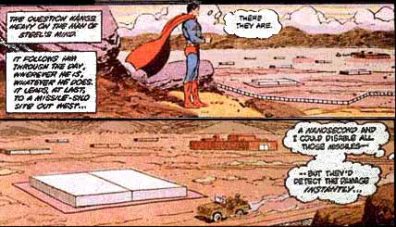

But Terminator 2 uses a technologically more advanced narrative metaphor: it is a video game. A kid—John—is at the controls. The targets pop up left and right, but the harm done them never seems serious. The cops are at worst kneecapped, and the T-1000 is as indestructible as a typical videogame adversary, continually reassembling himself for another round. The metaphor is underlined when, just before he meets the terminators, we see John playing the old anti-missile defence game “Missile Command” in a videogame gallery. Atari is listed in the credits; and of course Terminator 2 is also literally a videogame that you can play in your local arcade or at home on your Nintendo.21 (It’s also a rock video. Guns and Roses’ video of “You Could Be Mine,” contains scenes from both films.)

The entertainment and the sermon clash. There is little effort to reconcile them. By emphasizing the seriousness of the nuclear threat, Cameron has revealed to the thoughtful viewer the moral bankruptcy involved in trivializing violence in the rest of the film. By devoting by far the greatest part of the film to exciting chases, shootings, and explosions, he has undermined the earnest anti-war scenes. The net result is likely to be that the viewer’s appetite for mayhem is satisfied without his or her awareness of the danger of nuclear war being effectively aroused. Many action films present moralizing rationales for their mayhem of course, but it is rare for that rationale to be given the sort of emphasis and weight that Sarah’s visions have in Terminator 2.

The most important problem exists in both films, and that is the myth that nuclear weapons have a mind of their own. Skynet, as many have noted, is a version of SDI. Richard Corliss calls Terminator 2 “a Star Wars movie that is anti-Star Wars.”22 In fact, the term “hunter-killer” used in both films is taken directly from SDI plans for “hunter-killer” anti-satellite weapons. The Skynet myth reflects the (wholly justified) notion that nuclear weapons threaten their possessors as much as the enemy. As a metaphor it has great power. But it is also disempowering because it removes humanity from the equation. The fact is that nuclear weapons don’t cause nuclear wars: people do. Defense labs and the scientists who work in them are easy targets, but the real menaces are the politicians who have refused to accept responsibility for holding the whole world hostage at gunpoint and the voters who have elected them.

But in the event, the film may prove to be wiser than it at first seems. It became clear in 1991 that the U.S. and Soviet governments had finally gotten sufficiently afraid of their nuclear arsenals to start disposing of them. It took the collapse of the Soviet Union and the threat that missiles and bombs would fall into the hands of angry, vengeful Ukranians, Moldavians, and Latvians to precipitate the current anti-arms race in which both sides are frantically trying to match each other in the number and size of the weapons they can throw away.

It was Terminator 2’s misfortune to reach the screen just as its earnest sermon against the threat of nuclear annihilation was seeming more than ever irrelevant. Of all the problems threatening the world at the moment, imminent all-out nuclear war is not one. The proliferation of nuclear weapons in third-world countries poses different (and very serious) sorts of threats; but it is difficult any longer to imagine some fanatical dictator triggering a world-wide exchange of such magnitude that it could be called a nuclear holocaust. We need new myths to wrestle with that problem.

Endnotes:

1“Cling to Me.” November 13, 1984, p. 62.

2Cameron acknowledged the appeal of his villain in an interview with David Chute. “. . . you love to root for the bad guy; you want to see him get up again, you want to see him dumbfound the poor cops.” ” Three Guys in Three Dimensions,” Film Comment, February 1985, p. 59.

3 Young readers write in comments such as this, from a twelve-year-old enthusiast: “This comic is probably the best I have ever read because, and this is gonna sound morbid as hell, people die. I mean you don’t see them being ten inches away from an explosion and be okay.” Other fan comments: “I like the guns they use. I also like the part where the kid says, ‘You just bought a one way ticket to hell! my man.’ I really like the Plasma rifle.” Issue no. 11 of The Terminator . Chicago: Now Comics, August 1989, pp. 28-29. Publication of the Terminator comic books was taken over in August 1990 by Dark Horse comics, which produced a decidedly slicker and even more violent product for an evidently expanding market.

4Peter Fitting reads The Terminator as not as a frivolous nuclear war film, but as a fairly thoughtful metaphor for modern urban wastelands. See “Count Me Out/In: Post-Apocalyptic Visions in Recent Science Fiction Film,” CineAction! Winter 1987/88, p. 48.

5For more on the popularity of nuclear war imagery among eighties youth, see my article “Americans Learn to Love the Bomb,” New York Times, July 17, 1985, Section 1, p. 23, col. 1.

6“Narrative Entanglements: The Terminator, ” Film Quarterly, 43 (Winter 1989-90), p. 19. See also J. P. Telotte, “The Ghost in the Machine: Consciousness and the Science Fiction Film,” Western Humanities Review 42 (1988), pp.249-258. A more interesting discussion of this subject which includes Terminator 2 is Oliver Morton’s “A General Theory of Terminators,” The Modern Review 1 (Autumn 1991), pp. 32-33.

7Harlan Ellison saw in The Terminator the influence of his story “I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream” in which a misanthropic computer launches Armageddon, as well as others of his works; but although Cameron acknowledged some indebtedness (under the threat of a lawsuit), the parallels with The Forbin Project seem much more striking. See Max Rebeaux. “Harlan Ellison vs The Terminator: No More Mr. Nice Guy,” Cinéfantastique 15 (October 1985), pp. 4-5, 61.

8“ The Terminator: Beyond Classical Hollywood Narrative,” CineAction! Spring 1987, pp. 84-87.

9“Deconstructing The Terminator ,” Film Criticism 12 (1988), p. 46. See also Elayne Rapping. “Hollywood’s New ‘Feminist Heroines’.” Cineaste 14 (1986), pp. 4-9.

10“Child/Alien/Father: Patriarchal Crisis and Generic Exchange,” Camera Obscura 15 (1987): 29-31.]

11Beagles, Black Harrowers, etc.” August 12, 1991. p. 28.

12“Terminator 2.” People Weekly July 8, 1991, p. 13.

13“In the New ‘Terminator,’ The Forces of Good Seek Peace, Violently,” New York Times July 3, 1991, p. C11. Maslin makes several important criticisms of Terminator 2, but she does not deny that it is exciting.

14Kenneth Turan. “He said He’d Be Back.” Los Angeles Times , July 3, 1991. pp. F1, F6. Mick LaSalle. “‘Terminator 2’ Is the End-All.” San Francisco Chronicle, July 3, 1991, p. E1.

15See David Chute’s interview with Cameron, cited above. Cameron had thought up the idea of a shape-changing villain in working on the first film, but had to use “a more traditional kind of robot” because of budget constraints. See Shay, p. 29.

16This claim, repeated endlessly and uncritically in the press seems dubious. I would like to see the $20,000,000 figure adjusted for inflation and compared to the budgets of some of the old massive Bible epics.

17P. 19.

18“A General Theory of Terminators,” p. 33. A third film in which the threat is renewed is a very live possibility, of course, but it is worth noting that Randall Frakes’ novelization ends with a scene which confirms that the looming holocaust has been successfully averted. Terminator 2: Judgment Day. New York: Bantam, 1991, pp.237-240.

19The filmmakers studied old atomic bomb test footage in preparing the scene. See Shay, p. 113.

20It should be noted that the Terminators in both films are amazingly inefficient killing machines. They often move with glacial slowness at crucial moments and when aiming at their more important targets and miss most of the time. These are not “smart weapons.” But I wouldn’t make too much of the point. Their clumsiness is necessary to prevent them from annihilating the entire cast in seconds and wrecking the movie.

21Arcade game by Midway; Nintendo game by LJN, which also makes a hand-held Game Boy version. There is also a pinball game featuring a gleaming silver skull, by Williams. See Anonymous. “Terminator 2: Judgment Day: T2.” Electronic Gaming Monthly 4.12 (December 1991), “Masters of the Game” section, pp. 4 – 5 and Anonymous. “Terminator Pinball Wizardry” and “T-1000 Video Games Sweepstakes.” T2 (The Official Terminator 2: Judgment Day Movie Magazine. New York: Starlog Communications International, 1991, p. 4.

22Half a Terrific Terminator.” Newsweek July 8, 1991, p. 56.

Sources

Anonymous. “Terminator 2: Judgment Day: T2.” Electronic Gaming Monthly 4.12 (December 1991) “Masters of the Game” section, pp. 4 – 5.

Anonymous. “Terminator Pinball Wizardry” and “T-1000 Video Games Sweepstakes.” T2 (The Official Terminator 2: Judgment Day Movie Magazine. New York: Starlog Communications International, 1991, p. 4.

Brians, Paul. “Americans Learn to Love the Bomb,” New York Times July 17, 1985, Section 1, p. 23, col. 1.

Chute, David. “Three Guys in Three Dimensions.” Film Comment, February 1985, p. 55, 57-60.

Corliss, Richard. “Half a Terrific Terminator.” Newsweek July 8, 1991, p. 56.

Edelstein, David. “Cling to Me.” The Village Voice, November 13, 1984, p. 62.

Elayne Rapping. “Hollywood’s New ‘Feminist Heroines’.” Cineaste 14 (1986): 4-9.

Fitting, Peter. “Count Me Out/In: Post-Apocalyptic Visions in Recent Science Fiction Film,” CineAction! Winter 1987/88, pp. 42-51.

Fortier, Ron, writer. Thomas A. Tenney, artist. The Terminator no. 11 (August 1989), pp. 28-29.

Goscilo, Margaret. “Deconstructing The Terminator ,” Film Criticism 12 (1988): 37-52.

Kauffmann, Stanley. “Beagles, Black Harrowers, etc.” The New Republic August 12, 1991. p. 28-29.

LaSalle, Mick. “‘Terminator 2’ Is the End-All.” San Francisco Chronicle, July 3, 1991, p. E1.

Mann, Karen B. “Narrative Entanglements: The Terminator,” Film Quarterly, 43 (Winter 1989-90): 19.

Maslin, Janet. “In the New ‘Terminator,’ The Forces of Good Seek Peace, Violently,” New York Times July 3, 1991, p. C11.

Morton, Oliver. “A General Theory of Terminators,” The Modern Review 1 (Autumn 1991): 32-33

Necakov, Lillian. “ The Terminator: Beyond Classical Hollywood Narrative,” CineAction! Spring 1987, pp. 84-87.

Novak, Ralph. “Terminator 2.” People Weekly July 8, 1991, p. 13.

Rapping, Elayne. “Hollywood’s New ‘Feminist Heroines’.” Cineaste 14 (1986), pp. 4-9.

Rebeaux, Max. “Harlan Ellison vs The Terminator: No More Mr. Nice Guy,” Cinéfantastique 15 (October 1985): 4-5, 61.

Shay, Don and Jody Duncan. The Making of T2: Terminator 2: Judgment Day. New York: Bantam, 1991.

Sobchack, Vivian. “Child/Alien/Father: Patriarchal Crisis and Generic Exchange.” Camera Obscura 15 (1987): 6-35.

Telotte, J. P. “The Ghost in the Machine: Consciousness and the Science Fiction Film,” Western Humanities Review 42 (1988): 249-258.

Turan, Kenneth. “He said He’d Be Back.” Los Angeles Times , July 3, 1991. pp. F1, F6.

Last updated December 17, 2013